Famous All of My Life

with Quincy Troupe

Image Credit: Chris Felver

Before we officially meet, Quincy Troupe and I exchange a handful of telephone conversations. The first—and most telling—I receive unexpectedly while awaiting takeoff on a flight; I had sent him an email asking for an interview only minutes prior.

“I like to respond to people quickly,” he says. “You put your phone number in the email so I figured you wanted me to call.” Troupe explains to me that he is hesitant to do interviews, mainly because journalists “ask me stupid shit like, ‘so what do you do?’” he quipped. I listen attentively. Troupe commands a presence no matter the mode of communication. I assure him that I won’t ask stupid questions and that agreeing to the interview is entirely up to him. No hard feelings if he doesn’t want to do it. He responds, “Well I like the way you handled yourself in this conversation, so we can do it.”

A week or so later, I approach Troupe’s upper Manhattan building in the early afternoon. Following the detailed instructions he provided on our third call, I make my way to his apartment, which he accurately described as “very large.” Troupe and his wife Margaret have created a beautiful home in Harlem, one filled with paintings and sculpture, a multitude of books, prized photographs, and decades of love. Troupe is a big man, tall and imposing, with a confident sway that has arisen from years of being an award-winning poet, accomplished author, and celebrated professor. But, let’s be frank here, he embodied much of that confidence years prior to becoming a writer.

Quincy Thomas Troupe, Jr. was born on July 22, 1939 to parents Dorothy Smith and Quincy Troupe, Sr. (stylized professionally as Trouppe) in St. Louis, Missouri.

“I had no clue when I was growing up that I was going to be a writer,” says Troupe, noting that both his mother and father were avid book readers, which encouraged him to love books. Much like Troupe Sr., who was a star catcher in the Negro Baseball League, Troupe Jr. was a stand out athlete in both baseball and basketball, and had hopes of playing professionally. When he graduated from Beaumont High School in 1957, Troupe matriculated to Grambling State University on a basketball and baseball scholarship, but Troupe’s time there was short-lived.

“I got kicked out of Grambling for beating up people. See, I was from St. Louis. I was a different kind of person,” he says with a laugh. “I didn’t mind going upside people’s heads. I really didn’t.”

Part of it was simply "cultural clashes" with members of the football team, he notes. But looking back, Troupe now realizes that he was harboring anger, and some resentment, that he had not resolved. Before attending Beaumont, a predominantly white school, he attended Vashon High School, a place where students looked like him, where he fit in, and where people understood him. At Beaumont, students were often outright mean to him, and he resented being there. In addition, he deeply desired for his mother and father to reunite, but they had both moved on, and this was difficult for the young Troupe to reconcile.

When Troupe moved back home to St. Louis, his mother gave him a soft ultimatum. “She said to me ‘Look you can’t stay here. I love you, but you have to get some discipline.’ And she was the reason I joined the Army.”

From approximately 1962 to ’64, Troupe was a member of the All-Army Basketball team, stationed in Metz, France but traveling frequently to Paris and other European cities. And it was these two years that sparked Troupe’s writing career.

Pictured: Troupe with poet Maya Angelou and youngest son Porter. Photo courtesy of Troupe.

“I thought I was going to be a pro basketball player, but I hurt my knee twice. All of a sudden, I was laid up, when I had been scoring 35 points a game. I didn’t want to sit on the bench. What do I want to do that for?”

Troupe weighed his options to pass the time. He had a fondness for and history with music. Chuck Berry lived down the street from Troupe's home in the Greater Ville neighborhood, and his stepfather, China Brown, was a blues bass player, frequently filling the home with musicians. Troupe had experimented with the upright bass as well as an adolescent, but callouses formed on his fingers, interfering with his ability to feel and handle the basketball. For the budding athlete with professional aspirations, that was cause enough to set the instrument aside. With little interest in creating visual art, the injured Troupe turned to a pen and paper.

“I started writing a book about my sexual conquests all over Europe, because that is what was going on at the time. It was a terrible novel. I had this girlfriend, who was going to the Sorbonne, a really nice woman. I said to her ‘I’ve got this book, and it’s terrible. She said she would introduce me to a writer that was a good friend of her family’s.”

This family friend had no interest in reading Troupe’s fledging novel, but instead suggested that Troupe write poetry. And though he didn’t realize that prestige of his literary counselor at the time, Troupe had just received life-changing advice from famed French philosopher and author Jean Paul Sartre. So, Troupe dove into writing, both fiction and poetry, discovering that he loved writing “as much as I loved practicing jump shots. I could do it all day because I enjoyed making stuff up.”

After leaving the Army, he returned to St. Louis again, where his mother told him he had to “pull it together.”

“[St. Louis] made me stupid," Troupe tells me. He and his closest friends, several of whom were his cousins, frequently found themselves in precarious situations. And these situations usually involved physical altercations. "I had to get out of that environment, and I knew that, so I moved to Los Angeles.”

For six days in August 1965, African Americans rioted and protested police brutality in the South Los Angeles neighborhood of Watts, a tumultuous expression of anger and injustice that left the great Watts area, and many of its residents, devastated. A month later, Academy Award-winning screenwriter Budd Schulberg started the Watts Writers’ Workshops in response to the riots, aiming to provide a space where black and brown voices could convene and have serious dialogues about the societal ills plaguing the United States. Quincy Troupe was one of its first members.

“It fundamentally changed me, being in Los Angeles. It was the first time I had been around people who wrote poetry. I met Jayne Cortez, Stanley Crouch, and K. Curtis Lyle, who is still my friend to this day. I met [Alprentice] "Bunchy" Carter, who was the Southern California Defense Minister of the Black Panther Party, and so I got politicized while I was there. It was a great time for me.”

Photo courtesy of Quincy Troupe: L-R K. Curtis Lyle, Raspoet Ojenke, Troupe, Kamau Daáood.

He was dissecting Ralph Ellison, James Baldwin, Gabriel García Márquez, Amiri Baraka, Federico García Lorca, Pablo Neruda, Alan Ginsberg, and Aimé Césaire, among others, citing Neruda as a particularly big influence. “I studied poetry like you would study science,” Troupe remarked.

First and foremost, these were accomplished authors, which for Troupe meant “they knew how to put sentences together, and metaphors.” Writers who knew not only the nuts and bolts, but also the craft of poetry. He cites Octavio Paz’s The Bow and the Lyre for steering him in a new direction.

“When I read that, I thought about [poetry] in a different way. I was just writing mechanical forms at the time. So it changed me up. I discarded the forms and started writing free-verse, but I still had this formalistic training.”

This is also when Troupe began thinking seriously about success, and what that meant to him.

“In the beginning, I defined success as getting accomplished as a writer...I began to understand that poetry—and Alan Ginsberg told me this—that poets don’t make a lot of money. At the time I had met a lady in St. Louis and we had a couple of kids, and I had to make money. You can’t be idealistic about this stuff, you know. I didn’t want to be a dad who didn’t provide for his kids. So I thought ‘how can I do this and write at the same time?’

For Troupe, the answer was journalism. He enrolled at Los Angeles City College to learn more about the profession.

“I started writing for Los Angeles newspapers and did stringer stories. ‘Go down there and cover the parade! Go have an interview with the congressman, and you’re not getting a byline either,’ ” he laughs.

Quincy Troupe and wife Margaret Troupe. Photo by Vanity K.Gee

But Troupe didn’t care about the byline, because he was supporting his family and honing his craft, something he says he never stops doing. His experience as a journalist in Los Angeles helped him acquire the skills he would later use to edit and launch several publications, including Code Magazine in L.A where he served as the editorial director, and Black Renaissance at New York University, for which he and his wife Margaret currently produce.

In the late sixties, Troupe further developed his career in Los Angeles by becoming an educator, teaching at the Watts Writers’ Workshops, Directing the Malcolm X Center, and instructing at UCLA. Eventually, the Workshop selected a handful of poets, including Troupe, to do a 10-city poetry tour at colleges and universities across the country. This opportunity landed Troupe his first full-time teaching position at Ohio University in Athens.

“K. Curtis Lyle went to Washington University; I hated St. Louis and didn’t want to go back. Eugene Redmond and Oliver Jackson went to Oberlin, and I wanted to be in New York. [In the early seventies] I got an offer from CUNY-Staten Island and bolted.”

From there, he went where opportunity and good salaries led him, including teaching at Columbia University and UC-San Diego, authoring books of poetry and nonfiction, and continuing his journalistic pursuits. Troupe has taught many hundreds of students over the years, and according to him, they love him (and he, them). In fact, two of his former students were nominated for the 2017 Pulitzer Prize in poetry: Tyehimba Jess (nominated and won for his book Olio), and Campbell McGrath (nominated for his book XX).

“McGrath emailed me, asking what he thought it meant that two of my students were up for Pulitzers in the same year. I told him, ‘It says that I’m a great teacher, muthafucka!”

But for Quincy Troupe, success means more than teaching appointments and awards.

“My first yardstick was 20 books. ‘If I get 20 books,’ I thought, ‘I’ll be happy. I would have done my thing.’ But now I'm going to have about 26, 28 if I don't go down to the bone yards.” He laughs.

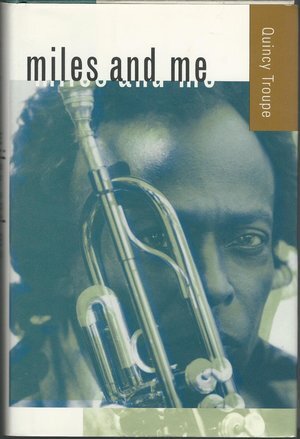

Professionally, he has won many awards and accolades. Troupe is undoubtedly most well-known for the work he has done with and about music legend Miles Davis. Davis’s autobiography, co-written with Troupe, was a bestseller and American Book Award winner in 1990. An audio program, The Miles Davis Radio Project, co-produced and co-written by Troupe, won a Peabody Award in 1991. His memoir about befriending Davis, Miles and Me, was also a bestseller.

Troupe’s poetry, both written and performed, have garnered him numerous awards and fellowships, including an American Book Award for his 1979 book of poetry, Snake Back Solos. He has also authored children’s books, and co-authored the autobiographies Earl the Pearl: My Story, and The Pursuit of Happyness, the latter of which was made into a major motion picture starring Will Smith. He also conducted the great thinker James Baldwin’s last interview. Of course, this list doesn’t include his recognition as an educator, editor, or journalist.

But it’s the people, the everyday man or woman responding to his work that also brings him a great sense of pride.

“People walk up to me on the street and are like, ‘Wow, Quincy Troupe? I loved this book of poetry!’ For me, that’s just great, [but] I don't walk around craving fame and recognition. I don't need people to recognize me all the time, because I was famous as a young athlete, and my daddy was famous. I've been famous all of my life. You know what I'm saying?”

Photo Credit: Vanity Gee. Troupe and musician Kelvyn Bell performing at El Taller Latino Americano.

Still, it is important for Troupe to meet certain professional goals for himself, especially in his career as a writer. If he isn’t on a tight deadline, Troupe wakes at five or six in the morning and begins working.

“I go to my study, which is across from my bedroom, and I go there and sit. The first thing I do is take out the garbage.” Troupe collects recyclables and trash from around the entire apartment, including his study, separates it in the kitchen, and then takes it to the dumpster. This morning meditation provides him with headspace to work through what he wants to write for the day.

“The last thing I do is go and get the papers from across the street. The NY Daily News and the NY Times.” Then, he sits down to write. “I’m constantly refurbishing, writing drafts back to back.” Aside from a few close friends, his wife Margaret provides feedback on his works in-progress, an editor he calls ‘cold-blooded.’

“She sees things that I don’t see because I’m too close to it.”

He writes drafts of poems long-form, but all other works are drafted on the computer. Troupe works seven days a week, and considers himself not a writer, but rather a cultural worker. When he compiles a book of poetry, he enjoys wearing his “editor’s hat,” considering the impressions that the first and last poems make on the reader, the tone they set for the entire poetic experience.

Our interview lasts for hours, four, to be exact, and I learn a lot about Quincy Troupe, especially his thoughts on what it means to be an American, and why so many of us struggle with that definition.**

“As a I grew as a person, I started to add on stuff. Black people come from all over the world. Black means different things in different places. Wines and Scotch, Ginsberg, Picasso, Neruda.” Troupe doesn’t move like most people, because “most of the people in the United States don't know what it is to be an American. A lot of white people don't know what it is, a lot of black people don't know what it is...they don't define it. What does that mean when you say you're an American? That means it's multicultural, multiracial, multi-religious, multi-dimensional, it's multi. It's a composite. So now, at this point, that's the way I move. I'm at home any place.”

His Latin American travels as a child with Troupe Sr., playing basketball in Europe, and now the vacations with his wife and close friends, have all helped developed Troupe’s sense of multi. For Troupe, being American also includes properly pairing wine with meals (which he learned during his time in France) and understanding the value of arts within culture and community. When Ethiopian painter Alexander “Skunder” Boghossian worked at Howard University, Troupe visited him in D.C. for several days, sleeping on his couch under one of Boghossian’s paintings, the first painting he ever really noticed.

Pictured: Quincy Trouppe, Sr.

“About two days later, I say [to Skunder] ‘I really like that painting,’ and asked him to give to me.” Skunder quickly corrected Troupe. “That’s the wrong thing to say,” Boghossian told him, and guided him towards the proper phrase of “How much does it cost?”

“I had never thought about buying paintings, and could not wrap my head around spending $2000 for a painting. A few months later, Boghossian was in New York, and took up residence with Troupe for a few days. He brought a package with him.

“This is the last painting I’ll give you,” Boghossian chided. “From now on, you have to buy it.” It was the painting that Troupe had admired.

“Skunder taught me how to look, to see things. We were on the subway and he said, ‘Quincy, Quincy, look!’ He was Ethiopian, a handsome, beautiful guy. The women loved him. He was a great painter. He tells me “Look down! Look down!’ I look down and see a rat going across the track. And I say to him ‘you mean that rat?’”

But Boghossian is directing his gaze to an oil slick, with a rainbow of colors shimmering through, and says to him “That’s a painting.” Troupe was amazed, and another world opened up for him, one that began to show how visual artists saw the world. It was in those moments with Boghossian that Troupe began to see art differently, to value it enough to purchase it, and to understand that visual art had a place in literature and poems.

Photo Credit: Thomas Sayers Ellis

“I don’t think that we as a people understand the importance of literature and poets, and painters and music.” (Troupe says this in relation to African Americans, but I believe this to be true for most Americans, considering the danger the arts face in K-12 schools, the lack of support for young people to follow careers in the arts, and the federal threat the NEA currently faces.)

“Art teaches us how to see ourselves in the world, whether it’s abstract or figurative. It is an expression of the culture, of the soul and the humanity and the beauty of the people…After I bought my first painting, I started to realize how much of an impact art can have in your life. How enriching it is for me to wake up and look…at all these [works] of Jacob Lawrence, Romare Bearden, Mildred Howard, Charles Olsen, Raymond Saunders, El Anatsui.”

Quincy Troupe’s work has enriched our lives, too.

Though Troupe wishes a few things in his life had gone differently, like graduating from college and the Poet Laureate debacle at UC-San Diego, he has lived a life largely free of guilt and regret. He befriended Miles Davis, has a professional career most people only dream of, has a family full of children and grandchildren, and a wife with whom he is his best self. Keeping sight of the different faces of success, professional and personal, has undoubtedly been a driving force of Troupe’s vast and incredible career.

“Nobody wants to die,” he started, “but I feel like if I died now, I’d be cool. I had a life well-lived.”

Troupe has two forthcoming books in 2018, both are works of poetry: Seductions and Ghost Voices, a long-form poem in 13 parts.